15.06.2018

From Flash games to historical strategies: a brief history of Clarus Victoria

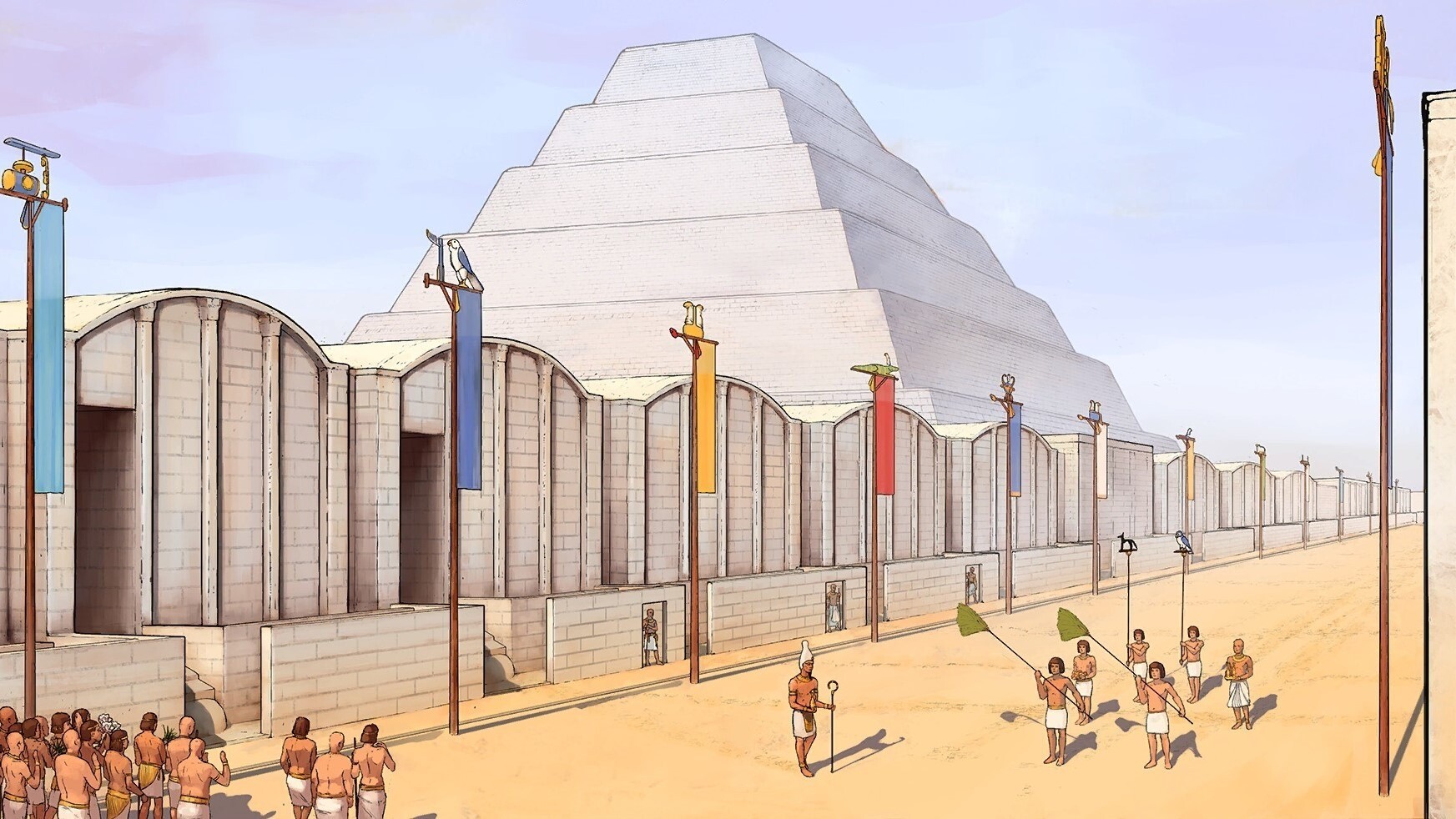

Hello everyone! My name is Mikhail Vasiliev. I am the head and game designer of Clarus Victoria. Recently we launched Egypt: Old Kingdom on Steam—a historical strategy about building pyramids, worshipping the gods, and solving a constant stream of challenges. Its main strength is historical authenticity and immersion made possible thanks to the help of Egyptologist consultants.

In this article I want to tell the story of Clarus Victoria—from the studio’s birth to the moment it turned into a thriving indie team that has sold roughly 200,000 copies of its games across platforms.

A Brief History of Clarus Victoria

The story of the studio begins with me. Before Clarus Victoria I worked in the games industry at companies like Nikita and Akella, but ethical questions constantly bothered me. What exactly are we giving to the next generation through games? Players spend billions of hours of their lives in virtual worlds—do they get anything meaningful from it? Those questions mattered to me more and more each year.

Stone Age

When I left my last job in early 2013, I started my first game: Pre-Civilization: Stone Age, dedicated to humanity’s beginnings. Later it became part of the Bronze Age bundle. I was completely on my own, which meant doing absolutely everything myself. Within four months I had to learn programming, drawing, animation, game design, carry out quick historical research, and assemble the game.

I also had to deal with localization, audio, and monetization. It was hard but exciting—a frenetic marathon with almost no days off, working 15 hours a day where learning and production blended together. The hardest part was realizing that I was alone: whenever I rested, development stopped.

From my previous game-dev experience I drew two important lessons for newcomers: do not rush head-first into a complex project, and never forget the value of core gameplay. My resources on Stone Age were limited and the game was simple, but I invested a lot into the core mechanics. Even so, friends and publishers who saw the game were skeptical and insisted it would not work.

The code was terrible—most programmers would have laughed on the floor. The art looked like a parody. An FGL reviewer (the old flash-game auction platform) gave it 6 out of 10, which meant the project was passable and sponsors would ignore it. I felt crushed and thought failure was inevitable.

The situation changed after I reached out to the lead curator at FGL, who rated the game 8/10. Things immediately improved: advertisers bought it, the project paid back instantly, and spread across the web. On Armor Games it received an 8.3/10.

Bronze Age

Working solo was psychologically difficult, so I invited my old friend Ilya Terentyev to join. We planned to create similar games to stabilize our finances. After some discussion we decided on a chronological sequel to Stone Age—Bronze Age.

Just like me, Ilya initially knew very little. We split responsibilities: he would draw while I worked on design and programming. In a couple of months we finished the game and even released it on mobile. Entering the mobile market was a source of endless pride for me. Only a few months earlier I barely understood what I was doing; now I could call myself a respectable “mobile developer.” It still took several more months to grasp everything. On Armor Games the game earned an 8.5/10.

Marble Age

At the end of 2013 we faced a choice: keep making small games or try to reach a new level of quality. Churning out many flash titles with quick payback was tempting, but we decided to move upward. That decision defined the development of Clarus Victoria: every project should not simply add content but also raise our standards. We began to evolve—strong ideas stayed, weak ideas were cut.

Development was difficult and our lack of experience showed. Mechanics were rebuilt many times. For example, trade and diplomacy were redone four times, costing months of work. On top of the Stone Age mechanics we added maps, battles, trials, and quests.

As with Stone Age, people doubted the game and I started to fear that I had overcomplicated the mechanics—that my ideas were getting unreasonable. Development dragged on for more than a year. Tension grew; money was running out, and we had to cut expenses to the bone.

We launched on mobile first and, after passing Steam Greenlight, released on Steam. For our modest budget Marble Age performed well. Players rated it higher than our previous games. We even experimented with an in-game currency to try free-to-play.

Revenue increased dramatically, but we did not understand who was paying. Perhaps kids were demanding (or taking) money from their parents, building a sense of impunity. That crossed our ethical line, so we removed the in-game currency and never returned to F2P. It might sound strange, but ethics mattered more to us.

Later we released a version on Armor Games, where it scored 8.6/10.

Predynastic Egypt

In the spring of 2014, after earning our first substantial money, we decided it was time to raise quality again. We wanted to start fresh and make games that were truly historical. We chose Egypt—the first real state and the cradle of our civilization.

We expanded the team. We found a Flash programmer we knew and started looking for artists to produce strong illustrations. The future looked predictable and exciting. Then a crazy idea appeared: what if we invited real Egyptologists to join as consultants? We assumed it would not work—that these academic stars would ignore us.

Nevertheless we called the Center for Egyptological Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences. The response was far warmer than expected: after learning about our plans, the Egyptologists agreed to help. They were interested in popularizing their knowledge. We were overjoyed; it felt like development would now run smoothly.

Reality, as usual, was harsh. Problems rained down: it took half a year to find good artists, the gameplay kept changing, the demo refused to become fun. After talking with the Egyptologists I had to throw away all the text I had written over several months and rewrite it halfway through development.

Finances were getting tight. Eight months after we started, the programmer told us his initial contract had ended and he would continue only for serious money or a revenue share. After some negotiation we realized that such terms would not work for the team, so we parted ways. As a parting shot he forbade us from using any of his code. The project was on the brink of failure.

But the darkest hour comes just before dawn, and miracles followed. Two wonderful artists—Ivan Beshkarev and Maxim Yakovenko—joined us. Then we found a new programmer, Egor Piskunov, who helped us rebuild the entire project in Unity within five months. Most of the decisions we made in those final months turned out correct; we devised approaches that dramatically optimized our work.

The game launched on Steam as Pre-Civilization Egypt. It was a success, received ratings above 91%, and earned back its budget within a couple of months. The historical authenticity set a high bar: we even received thank-you letters from people in Egyptology and education. So far we have sold about 60,000 copies on Steam and mobile—small for big studios, but a lot for us.

However, a week after release, Civilization VI came out. A few weeks later our game was removed from Steam without warning.

We eventually learned that Take-Two owns the Civilization trademark. They contacted Steam, Google, and Apple, and the stores blocked us almost instantly—even in search results. We apparently had no right to use the word “Civilization.” Store logic is simple: always side with large publishers and disclaim responsibility. If you want to sue—go to court. We escaped the situation only by renaming our games.

We did not mourn for long; honestly, changing the names made the games better. The project became Predynastic Egypt.

Old Kingdom

During the crises around Predynastic Egypt I started searching for answers to the gameplay issues that bothered me. Why is development so hard every time? Why does making a game feel like magic where you never know the result? What happens if we keep raising the bar forever?

I asked myself what the ideal game truly is. Where do our games stand? Where should we go next? Over the next year I read dozens of books on game theory, systems analysis, and more, drafting concepts and long-term plans. The new project set an ambitious goal: to build a historically accurate game about the great age of the pyramids.

I wanted to reach a truly high level—in design, authenticity, and atmosphere. So the first six months were wild experimentation with genres, mechanics, and technology.

The process dragged on until Ilya stopped it. Sadly he decided to leave Clarus Victoria and look for his own path outside the industry. He continued consulting us, but funding and PR (his area) suddenly became limited. After that the concept of the new game took shape within a few days: we took Predynastic Egypt and added only the most necessary and obvious elements we could afford on the path toward our ideal game.

Expanding the team should have solved the most pressing development problems. We temporarily lost Egor from the previous project (he moved abroad) and brought in new programmers Anton Shcherbakov and Georgy Ryaposov. I also hired three design assistants. My logic was simple: more people meant faster development.

That strategy turned out to be a major mistake and cost us months. The game’s design was too auteur and complex to delegate, so I had to reassign the team and finish the design myself. A similar story happened on the programming side where people did not click. On the plus side, we added a dedicated PR specialist, Polina Kuzmina, who speaks Chinese in addition to Russian and English—important because our games had become most popular in China.

Another huge issue was the gameplay logic. Our games always had complex logic code, but Egypt: Old Kingdom had about 1,500 logic files, making it extremely difficult to program. Development stretched from the planned ten months to almost a year and a half. For scale: in the time it took to make Old Kingdom, we could have produced three to five Predynastic Egypt-sized projects.

Polishing also dragged on. As funds dwindled we decided to release. We tested as best we could, but even when it was time to hit “Publish” on Steam I was unsure the game was ready. Only then did we start sending it to reviewers and press—something we had planned to do much earlier.

I knew late PR was a mistake, but the pressure was enormous and I did not want to delay further. Sales did not go as well as they could have. Overall the project looked successful—more than half the budget returned in a few days—but things would have been better had we launched PR earlier. In hindsight, we probably should have delayed release by a month.

Our project was supported by helpers, volunteers, fans, and friendly YouTubers. Thanks to them and everyone who has bought—or plans to buy—the game and is reading these lines. Without you none of this would have happened. The more like-minded people we have, the easier it is to make games. That is our main source of inspiration and a sign we are on the right path.

Conclusions and Advice

Here is what I would suggest to others:

- Be optimistic and love what you do. If something does not work out, look for the path that speaks to your heart. We were on the edge more than once; enthusiasm kept us alive.

- If you are unsure, start small. It is better to do less—but do it well.

- Seek knowledge and skills. Study before you begin, but do not drown in theory—it is endless. Each level of tasks requires its own level of knowledge; basics are enough for simple tasks.

- Finances matter. Do not plan expenses you cannot carry. Early on, if you are uncertain, start with no money. Level up first, invest later.

- Value your time—it is worth more than money. Avoid development swamps. Even successful, high-earning projects can stall.

- Find a good team. Good projects appear when good people do their jobs well.

- If you are making a game, never neglect marketing—but do not put PR above the game itself.

If you would like to trace our evolution yourself, try our games. Later we will talk in more detail about the mechanics of Old Kingdom and how we approach historical authenticity.